A (no name) Artist Tells His Story…

Our artist wishes to remain anonymous, but I am so grateful he has agreed to share some of his illustrations with us. A select handful have been chosen and featured below. They provide insight into life as a refugee and describe hardships most of us can not imagine.

Page 4. Uprooted. This is the story of a family, my family, uprooted by war and shattered by violence. This is the story of our struggle to survive and my search for peace and meaning.

My family dispersed around the world seeking refuge where it was offered. Some prospered. Some did not. We are but only a small fraction of the millions of refugees around the world today trying to make a new home in unfamiliar and sometimes unfriendly environments.

Unlike an immigrant, who chooses to leave their country when they are ready, a refugee is forced to leave with little or no preparation. Surviving is not just about making a living and assimilating, but also about dealing with the aftermath of shock, trauma, broken families, and haunting memories.

I hope this story can help my family, myself and others move on from our pasts.

I hope I can help others overcome their inner turmoil, whether they’re a refugee from another country, an outcast in their own land, or abandoned by their own family. My message to them, to you, is to never give up.

Page 9b. Birthdate unknown. I was born on the floor of a bamboo hut around 4am in the year of the dragon in the 8th month. The exact day is unknown. They knew the month by the change in the seasons and crops. According to my mother, there were no calendars around, at least ones that were accessible to them. A couple of years before I was born, there was a civil war and the new regime relocated almost all of the country’s citizens into forced labor camps to produce rice. The workers were fed just a few bowls of watery rice porridge a day. Some vegetables were mixed in, but not enough. People were still hungry and many starved. Our camp was called Osalao (this is not the official spelling, just the phonetic spelling. I couldn’t find a record of it anywhere online. I will update as I learn more.) Osalao was a 2 hour walk from Battambang, the nearest major city. Another two-hour walk away was Moung, where my mother grew up.

According to my eldest brother, when my family arrived at the camp, the soldiers pointed to a plot of land and told us and other families in our group to build our own living quarters. They had no tools. The bamboo floors were uneven. They used leaves for the roofs. They had no nails. They used twine. He said that we used nets to keep the mosquitos out, but it only worked about 60% of the time. A hole was cut in the bamboo floor where the stove would be placed. Those who tried to cook on the bamboo burned their houses. He said the roof, surprisingly, did not leak. However, insects always came in through gaps in the walls.

My brother remembers that there were no medicine, no gloves, no doctors, no IV, no bed. He remembers that our mother was in a lot of excruciating pain. The worst pain you can imagine, he says. There was no light. They used a small lamp and or candles. They used hot water to sanitize things. Thank god there were no complications. I think it was a miracle and you are so blessed to be a healthy baby, he says.

My parents already had one daughter and two sons. I would be the fourth. I was too young to help with anything. What a burden I must have been. What a blessing my mother survived.

Page 9. Killing Fields. I don’t remember any of it. The very few memories I have of Cambodia luckily are only of random images of lying down on pebbles, swinging in a hammock, and standing naked in the rain. According to my family, they worked in the fields for nearly three years with no medical attention, medicine, and little food. They were served one bowl of watered-down rice a day per person. To stay live, people had to sneak into the woods to gather whatever food they could find such as frogs, turtles, crickets, other insects and honey at the risk of being caught and severely punished by the soldiers. Some like my youngest uncle were bitten by poisonous snakes or scorpions. From what I’ve read, the Khmer Rouge communist regime took over the country in 1974 and enlisted farmers and children to force it’s own people into labor camps and eliminate anyone who had an education, spoke foreign languages or believed in religion. Their motto was “To keep you is no benefit. To destroy you is no loss.” I just can’t imagine living without knowing when, how and if the suffering would end. I can’t imagine my mother and father trying to keep their four children alive. My three older siblings were barely 10 years old when they were sent to the fields. The exact death toll is uncertain. Estimates vary from 1 to 3 out of 7 million who died between 1974 and 1980. I lost a grandfather, two uncles, an aunt and a cousin.

Page 15. Fleeting moments. For a brief moment after we arrived in our new country and before being swallowed up by the urban jungle, my family shared these rare moments of joy at a large nearby park in Philadelphia called FDR park.

These were special moments before the stress of adjusting to a new land, language and life took it’s toll on our family relationships. These were the few times we were together before my father would be gone for most of our waking hours.

We found comfort in this park along with many other refugees. It reminded us of the land we left 8,000 miles away.

We picnicked here. We climbed trees and ate green crab apples with salt and chili pepper. One neighborhood friend from Laos gave me a chili pepper so hot, I almost fell off of the tree. We hunted for and played with lost and discarded tennis balls outside of the tennis courts.

There was also a small lake there. My brothers once caught a snapping turtle that they tossed back. We also skipped stones and fished there. My brothers and cousins were really good at fishing. We didn’t have any fishing poles or equipment. We used fishing lines people discarded and were half buried in the dirt near the edges of the lake. Some still had hooks attached. We used a tree branch for a pole, a twig as a floater and dug up the worms as bait. It worked. Sometimes we would cook the fish for dinner later that night.

I wish we had more of these moments in our lives.

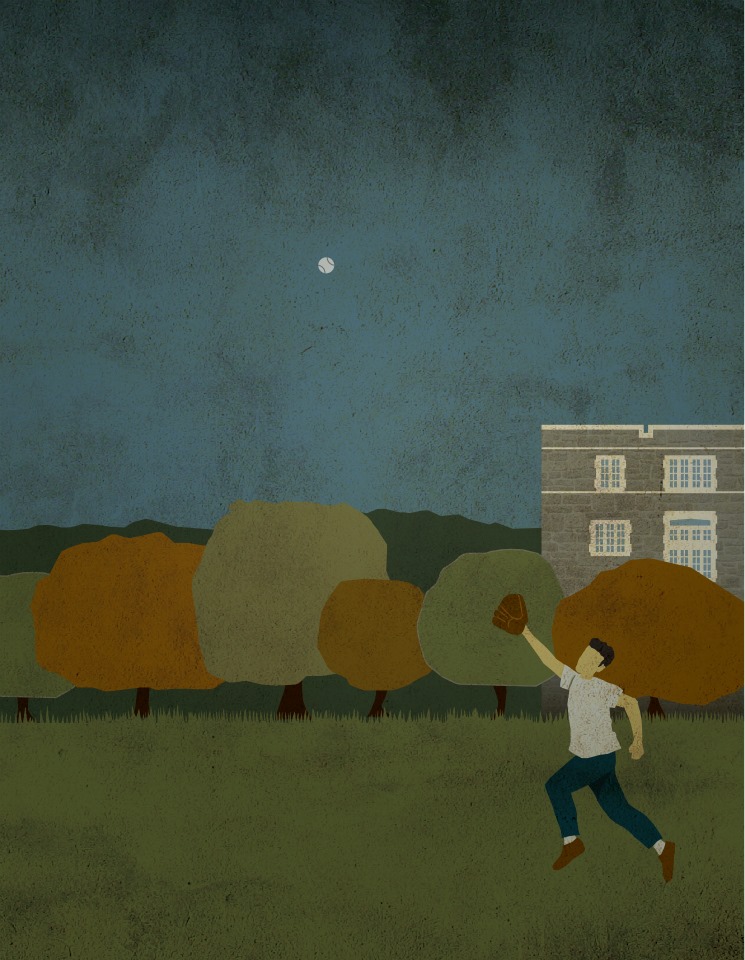

Page 13c. Almost flushed down the toilet. I was 6 years old. I had just transferred from one South Philly elementary school to another. It was closer to home. This one was both an elementary and middle school. One day I got lost looking for the bathroom. I wandered down a long dimly lit hallway. Everything looked so big. I felt so small. I finally found the bathroom, but there were about 3 older, perhaps teenage, boys there. They gave me a funny look then quickly grabbed me, took me to a stall, held me upside down and threatened to flush me down the toilet. I saw the water swirling over and over just inches away from my nose. They kept flushing and flushing. I was terrified. I screamed, yelled and kicked. A couple of long minutes later, they let me down and I could hear them laughing as I ran out. I didn’t say anything to the school nor to my parents. I don’t know why I didn’t. I was just happy I escaped.

I would not always have such luck as I got older. I stood out. My siblings stood out. We looked different than the rest of the people in our neighborhood and city. We acted differently. We dressed differently. We were easy targets. We were small in number. We were the new minority.

I did nothing to deserve this. I’ve never met these boys and did no harm to them. This was random, but who cares, right? Looking back, it was probably just a prank. I just needed to suck it up and toughen up. What I went through paled in comparison to what my parents went through in the war and labor camps.

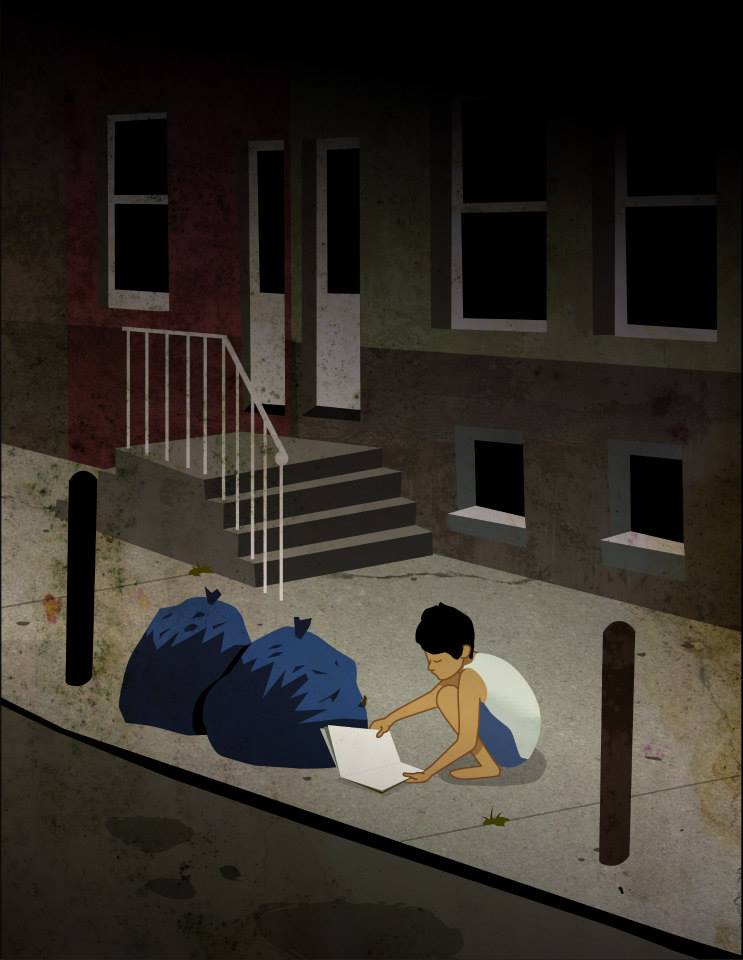

Page 14. My siblings and I didn’t have a lot of toys growing up. We didn’t celebrate birthdays either. We weren’t sad because of it. We made the most of what we had. We played hide-and-seek on the streets and hid under cars in the dark. We played with bottle caps and sticks. We climbed trees and trash picked. Sometimes finding treasures like this coloring book. One day when I was four or five years old, while wandering the streets barefoot as we usually did our first years here, I saw it sticking out of a trash bag. It was beautiful and there were unbelievably a few pages still left uncolored. I was so happy sitting there flipping through the pages. It was one of the best memories of my childhood.

Page 15b. A church in South Philadelphia called Calvary St. Paul sponsored my family to America from the refugee camps in Thailand. I remembered learning about Christianity on Saturday mornings. I learned about God, Adam, Eve, David, Moses, Jesus and more. My father was a janitor at the church. I remember playing the role of Elijah when I was about 5 or 6 years old. We stopped going to church when we moved to the Bronx a few years later, but these biblical stories stayed with me throughout my teenage years. This was the only consistent religious education I had. My mother was Buddhist, but by culture. She never explained fully what it meant and we did not go to any Buddhist temples. I tried reading about different religions, but I still found no answers. I continue to wrestle with my faith and spirituality.

Page 16c. Education was our main ticket out. Starting in middle school, we woke up at 6:30AM and rode the New York subways and buses 50 minutes and 11 miles away to a better school in a different borough. We took the D train at Kingsbridge Road in the Bronx, transferred to the B train in Harlem, and took the city bus across Central Park. We didn’t have time for breakfast and often fell asleep on the trains. I loved sleeping on the trains and somehow managed to never miss a stop. On good days I was able to ride with my older brother and best friend. We were not the only children doing this. There were many in New York, especially my Prep for Prep peers, doing the same thing and some commuting up to two hours each way. God bless them.

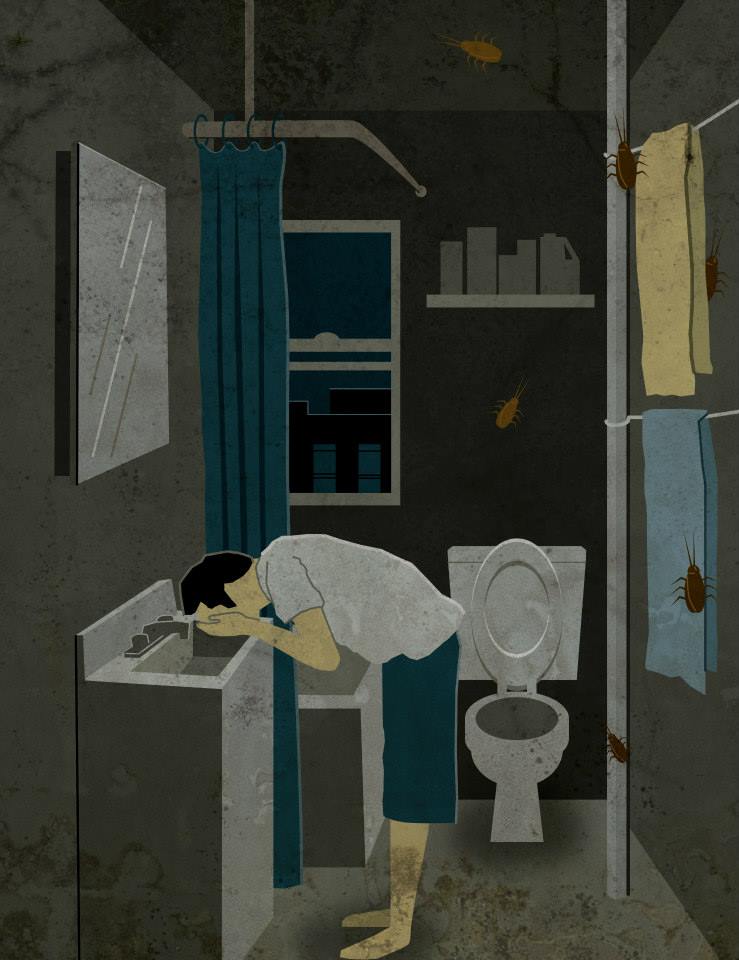

Page 16d. Roaches. Big roaches. Not the rice grain-sized ones, but the thumb-sized ones. The wide fat ones. The ones that can fly across a room. (Please do not read any further if you get squeamish). The ones that come back to life after being stepped on and thrown into the trash. New York roaches. Bronx roaches. They slowly invaded our apartment. Not just roaches, mice too. Not shy lab mice, but bold city thug mice that could jump a foot and a half high out of a bathtub, sit and watch tv in front of you, eat the rice in your rice bag and live in your sofa. We had traps, but they weren’t enough. One terrible day, I had to slowly squeeze the life out of one mice I caught inside our 50-lb bag of rice. If I tried to catch it on it’s way out of the bag, it would have escaped. It was a horrible feeling. A piece of me died that day and haunts me every time I think about it. I also remember my grandmother made some instant noodles and a bloated half inch roach floated to the top. I looked to her for advice. She said it was fine. She scooped out the roach and I ate the ramen. It was disgusting, but I was hungry.

These creatures came out in the middle of the night when we went to the bathroom and would scurry away when we turned on the light. I had a little heart attack with each encounter and the encounters became more and more frequent. No matter how many we killed, they just came back. The roaches crawled from under our hanging towels. It felt like we were living in a Hitchcock or Stephen King movie. I never saw my five foot nine 18-yr-old, stronger, older brother fly so fast out of bed in fear as when a roach flew at him while he was trying to sleep on the top bunk bed. Eventually we would get used to them. How can I hate them? They were trying to survive as much as we were.

Page 16h. Christmas. I was about 11, 12 or 13 years old. I don’t remember exactly. I don’t have pictures of it. It was a couple of weeks after Christmas, I found the top third of a broken fake Christmas tree near the garbage bags outside on the sidewalk and brought it upstairs. I stuck it in a can filled with loose change and or rice and decorated it. It was our first Christmas tree. My father was not religious. My mother did not grow up Christian.

In songs, on tv and in the movies, the Christmas tree was such a symbol of joy. I wanted to bring some of that joy to our apartment. My parents celebrated the Lunar New Year, which unfortunately was not as prevalent in the media so I didn’t really understand it.

Another year, I walked to a toy store one cold dark evening about a mile away to try to buy gifts for the first time for my siblings and parents. My sneakers were soaked and my toes frozen from the wet city snow. We didn’t have boots.

Once in the store, I must have walked down every aisle four or five times trying to figure out what I could buy for $10 for my family. Unfortunately, not much.

I finally settled for a bingo game, not a fancy one, just one made of perforated paper that you had to rip up yourself. The other board games like Monopoly, Life or Chutes and Ladders would’ve been great for all of us, but it was more than $10.

That night, since the bingo game was so small, I decided to just give it to my younger sibling instead of giving to all of my siblings.

He was so happy. Later that night, he gave me something. I was surprised since we didn’t have much and I didn’t think he went to the store. He was still too young. I didn’t even expect him to give anything back.I unwrapped it and it was the bingo game I had just given him earlier. We opened it that night and played with it. For a brief moment we felt the spirit.

After that, Christmas never caught on in our household. We didn’t exchange gifts much.

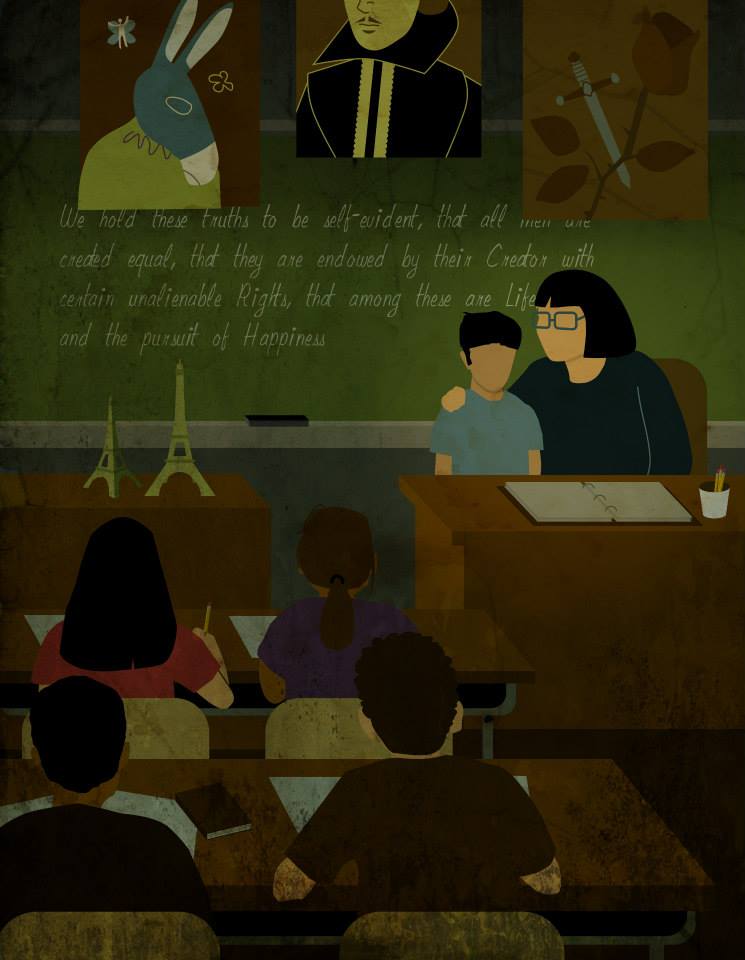

Page 17b. Gifted. In the middle of my fourth grade my family moved from South Philadelphia to the Bronx and I attended P.S. (Public School) 246. My older brother was accepted to the 5th/6th grade gifted class taught by Mrs. Marlene Losak. I did not get accepted into the program until I was in 6th grade and my younger brother was accepted a few years later. There were many people who had an impact on my life, but if there was one who had the greatest impact on my family, it was Mrs. Losak. She believed in us. She pushed us. She loved us. She was a Jewish woman who didn’t care what ethnicity, religion, or from what socioeconomic background we, her students, were. She only wanted to show us how much greater we could become. Though we were considered the gifted students, it truly took a gifted teacher to see and cultivate the gift in her students. I visited her almost every year from 7th grade to college just to say thank you and give her a big hug. Since college, I’ve thought about her every year and dreamed about how I could repay her back. I dreamed about paying for a vacation for her, or a starting a scholarship in her name or something to say thank you. I was waiting until I was rich and successful. I was waiting until I finished this illustration. Unfortunately I waited too long. I got a message from my brother yesterday that she just passed away on June 5th and my heart sank. I miss you, Mrs. Losak and I/we love/loved you very much. I wish you knew how much you did for us. I would not be here today if it wasn’t for you.

Page 18h. Forgotten Valor. During my elementary and middle school years, I learned on TV, in magazines and in movies, about so many great citizens who contributed to America from the founding fathers to Martin Luther King, Jr., but there was so little mention of Asian American or Latino/Hispanic American citizens.

In my senior year of High School, I signed up for an independent study class so I could focus on Asian American history. The local public library, at that time, had only a handful of books about the subject. What little information I was exposed to made me want to learn more.

Throughout the course, I discovered so many amazing stories about the contributions made by Asian Americans and the challenges they faced from being interned to being excluded from immigration. My studies also exposed me to other citizens who contributed despite being casted aside by their fellow countrymen, such as the African American Tuskegee Airmen, who, though segregated and discriminated against, fought for America during World War II.

I was never more into my studies than at this time and for this class. I eagerly shared these stories with my family, friends and anyone willing to listen.

In terms of Asian America, some of my favorite stories were of the Chinese Americans who helped build the Transcontinental railroad in the 1860s, the Filipinos who arrived in Louisiana in the 1760s, and especially the 442nd Regiment. In short, the 442nd were comprised of Japanese American soldiers who were one of the most highly decorated regiments in WWII. Ironically, while they were helping to rescue Jews who were interned in Nazi concentration camps overseas, their families were being wrongfully imprisoned in internment camps in their homeland of America. These were stories we didn’t hear about.

Through my new lens, I could see how this mis– or lack of representation could affect people’s opinion of others. This was around the time the popular reality police show, COPS, was on TV. It kept showing a disproportionate amount of videos of black people being arrested. My mother watched it so much she even knew the theme song, “Bad Boys, bad boys, what cha gonna do when they come for you…” I would tell my mother to not stereotype people based on what she saw on TV. I talked to her about MLK and many others who fought for our rights.

It’s interesting how communities can be ignored and silenced, almost erased from history. All of us have faced struggles including early European American immigrants. We take it for granted that the truth will prevail and that everyone’s interested in the truth. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. One has to proactively fight for, cherish, share, teach, and celebrate our contributions. We should remember the sacrifices and honor the valor of all immigrants and citizens who came before us.

Page 18i. Great divide. My parents grew up in Cambodia. Their parents grew up in China. My siblings and I grew up in America. We were three different generations who grew up in 3 different countries, each with it’s own different language and culture.

My parents did not speak English well, the official language of America, where we moved to when I was three years old. They sent me and my siblings to learn Mandarin Chinese on Saturdays for a couple of years, but at home, my parents spoke Khmer and a little bit of a few different other dialects of Chinese, like Diojiu (Teochew) and Cantonese.

Over time, their English did not get much better nor did my fluency in their languages. In school, I would have to take Latin and French classes too — two more languages they didn’t know.

We grew apart. We would try to communicate, but our discussions became more and more shallow. We knew less and less about each other. We did not go deep into topics. I wish I could’ve told them more about all the things I was going through, all the things I was learning and all the questions I had. I did not have the vocabulary to do so.

If language was a key to another’s heart and mind, we were both locking each other out. I was losing touch with my parents’ culture.

My parents’ customs at home were different than that of my teachers’ and classmates’ customs at school. At home, making eye contact was considered rude. We did not debate with or challenge authority. We did not show our emotions. We hardly said, “I love you” or gave hugs.

My parents grew up on farms in a third world country an ocean away. I was growing up in a major city in a first world superpower country. Though we lived under the same roof, we were worlds apart.

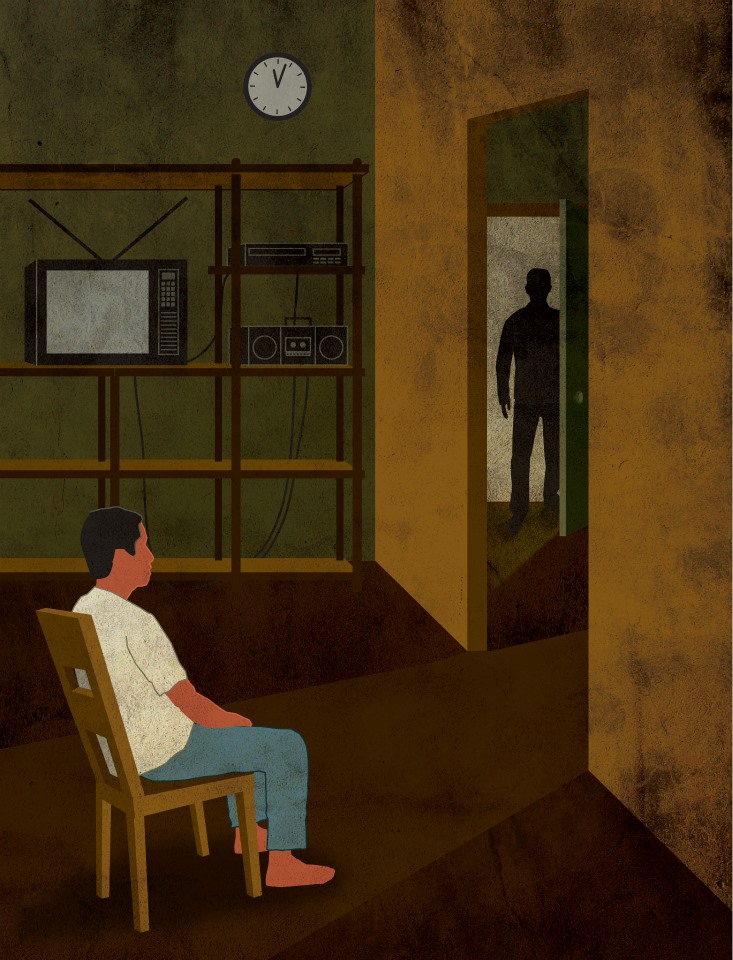

Page 19b. Dad. Didn’t see him much. He worked a lot. He was born in Cambodia, came to America when he was 33 and raised 5 of us kids with little to minimal knowledge of English. He speaks a few dialects of Chinese, Cambodian (Khmer), some Vietnamese and Thai. We are refugees, which are different from immigrants. Refugees usually flee a war or disaster and do not know which country they will be sent to. Immigrants usually choose a country and are mentally, academically and somewhat financially prepared. We were not. My father was the eldest of about 10 siblings. His family was separated in the war. His siblings and parents ended up in France along with his parents, except for one brother, who lived in Queens. My father did the best he could. In New York, he worked late and didn’t come home until after 10, 11 and sometimes later.

On his way home one night, he was attacked and hospitalized for days. In another incident, he was chased on foot by a carjacker and shot at, but luckily wasn’t hit. These are just a few of the stories.

My mother always told me that I looked and acted like him, a person she was always at odds with. At some point she couldn’t wait up for him as often anymore. She had to wake up early to get our breakfast ready so she asked me to wait up for him and I did. He would come home so late, there wouldn’t be parking available on the streets. There were too many tenants in too many buildings in a small area and hardly any parking lots nearby. He would have to circle around over and over so much that he would forget where he parked. In the morning, he would send my poor older brother to find his car. I wanted to spend time with him so I went with him to deliver groceries. Sometimes he’d go up into the building and I would wait in the car. On some of the deliveries, I would wait for a long time, to the point where I just wanted to ditch the car and run home. Since there was no parking, he had to double park. My job was to make sure we didn’t get a ticket.

My brother said he carried me on his back, when I was about 3 years old, the whole time we were escaping the war in Cambodia. Thank you dad, I owe you my life.

Page 20. Failure. Many, many times I’ve failed. Whether it’s trying out for a sports team, applying for a job, running for a leadership position, helping a loved one through difficult times, making and keeping friends, I’ve failed. It hurts. It’s painful. You just have to learn from the experience, pick up the pieces and move on. Surround yourself with loving and supportive people. Seek them out. To them, I owe all my success.